Citizen Science: A Partnership Between Everyday People & Professional Scientists

Last summer, my family and I were strolling along a beach in South Carolina and noticed beautiful shells that were washing up onto the beach with each wave. The creatures would quickly burrow themselves, and their protective shells, into the wet sand. I took a few photos and posted them on Facebook. I commented, “Wow, these shells are beautiful, anybody know what they are?” Honestly, I didn’t expect much of a response. Instead, I received a number of comments about what species of marine gastropod it was and one oceanographer friend exclaimed, “I am so envious, where are you? I have always wanted to see one of those!”

Last summer, my family and I were strolling along a beach in South Carolina and noticed beautiful shells that were washing up onto the beach with each wave. The creatures would quickly burrow themselves, and their protective shells, into the wet sand. I took a few photos and posted them on Facebook. I commented, “Wow, these shells are beautiful, anybody know what they are?” Honestly, I didn’t expect much of a response. Instead, I received a number of comments about what species of marine gastropod it was and one oceanographer friend exclaimed, “I am so envious, where are you? I have always wanted to see one of those!”

The now famous Olive snail

I am not scientist, but I learned that my observations, questions and photos were of value to the scientists who make a living studying, tracking, and monitoring our amazing ocean life. Without knowing it, I was acting as a “citizen scientist”. Citizen science can mean anything from people simply observing natural events and characteristics to a full-fledged revolution in ‘science’ that establishes the important social role of learning about the world we live in. Citizen science can enable professionally-trained scientists to leverage the efforts of groups of people distributed widely, or a way to leverage the brains, experience, and insights of the world’s people to advance understanding.

In order for citizen science data to be used and usable, it is important that the information collected is credible and needed by scientists. Fortunately, the value of citizen science is being recognized by individuals and organizations that are in a position to get the word out. Programs are being developed by government agencies and nonprofits, like ours, to train people interested in getting involved and to develop Web-based applications where citizen scientists can share their findings.

Copyright REEF.org

Mote Marine Laboratory, in conjunction with the US government and numerous universities, has developed a program called the Marine Ecosystem Event Response and Assessment Program (MEERA). MEERA is a community-based reporting network, which enables ANYONE on the water to report on unusual biological events in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and surrounding waters. Another online tool, supported by the National Geographic Society and called Project Noah, enables nature lovers and citizen scientists to explore and document their natural world. These tools are a powerful source of information that can be used for science research and educational programs that promote wildlife awareness and preserve biodiversity.

In tandem with our geotourism based programs, the Marine & Oceanic Sustainability Foundation (MOSF) is developing training and participatory programs that enable ocean lovers to get involved in hands-on citizen science activities. All of our programs are marine conservation focused and include activities ranging from the identification and protection of sea turtle nesting locations to scuba diving trips on which divers help reduce the population of invasive species, like the lionfish, on coral reefs. MOSF’s first geotourism and citizen science programs are already being developed and will be launched in the Caribbean region.

Turtle Research

Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology has an established citizen-science program that has more than 200,000 individual people contributing data each year; data collection on this vast of a scale was only recently unimaginable. Cornell’s scientists are using these data to determine how birds are affected by habitat loss, pollution, and disease. They trace bird migration and document long-term changes in bird numbers across the North American continent. The results have been used to create management guidelines for birds, investigate the effects of acid rain and climate change, and advocate for the protection of declining species.

Citizen science is very important! It helps scientists attain information and answer questions about topics that they may not have the resources to collect on their own. Citizen science encompasses a broad range of topics, geographic settings, and strategies. Some projects are confined to a single species and locations, like loggerhead sea turtles on an specific island in the Bahamas, while others are global in scope. On any scale, citizen science creates opportunities for people of all ages to connect with the natural world, gain scientific skills, and learn key science concepts.

A survey done in the 1970s estimated that there were around 10,000 of these penguins, but current surveys show that there are only about 1,000 breeding pairs left. Scientists think that about 77% of the population died in 1982 and 1983 when the islands experienced unusual weather, which caused a food shortage for the penguins. They seem to be slowly rebuilding their population.

A survey done in the 1970s estimated that there were around 10,000 of these penguins, but current surveys show that there are only about 1,000 breeding pairs left. Scientists think that about 77% of the population died in 1982 and 1983 when the islands experienced unusual weather, which caused a food shortage for the penguins. They seem to be slowly rebuilding their population. The penguins mostly eat small fish like mullet and sardines. Unfortunately, because they are so small they have many predators. On land, crabs, snakes, owls, and hawks pick on the little penguins; in the sea, sharks, fur seals, and sea lions can attack them. It can be a rough life, but these penguins seem to enjoy their tropical paradise.

The penguins mostly eat small fish like mullet and sardines. Unfortunately, because they are so small they have many predators. On land, crabs, snakes, owls, and hawks pick on the little penguins; in the sea, sharks, fur seals, and sea lions can attack them. It can be a rough life, but these penguins seem to enjoy their tropical paradise.

MOSF is committed to working with local teachers, students, and community groups. Through outreach programs like this, people will gain a better understanding of how they are affecting their marine habitats and how they can get involved to assure their long-term health and sustainability.

MOSF is committed to working with local teachers, students, and community groups. Through outreach programs like this, people will gain a better understanding of how they are affecting their marine habitats and how they can get involved to assure their long-term health and sustainability.

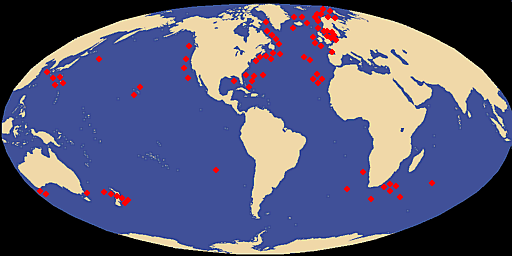

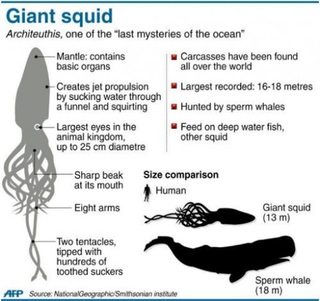

You would think an animal the size of a school bus would be easy to find. Yet the giant squid, which weighs over a ton and is over 42 feet in length, is still one of the biggest mysteries of the ocean. Scientists all over the world are trying to learn more about this elusive animal. Part of the reason that so little is known about them is because they live in the deepest parts of the ocean. They are so deep that it takes about 2 hours to go up and down in a submarine. It has only been recently that they have had technology advanced enough to go that deep and it is still very expensive.

You would think an animal the size of a school bus would be easy to find. Yet the giant squid, which weighs over a ton and is over 42 feet in length, is still one of the biggest mysteries of the ocean. Scientists all over the world are trying to learn more about this elusive animal. Part of the reason that so little is known about them is because they live in the deepest parts of the ocean. They are so deep that it takes about 2 hours to go up and down in a submarine. It has only been recently that they have had technology advanced enough to go that deep and it is still very expensive.